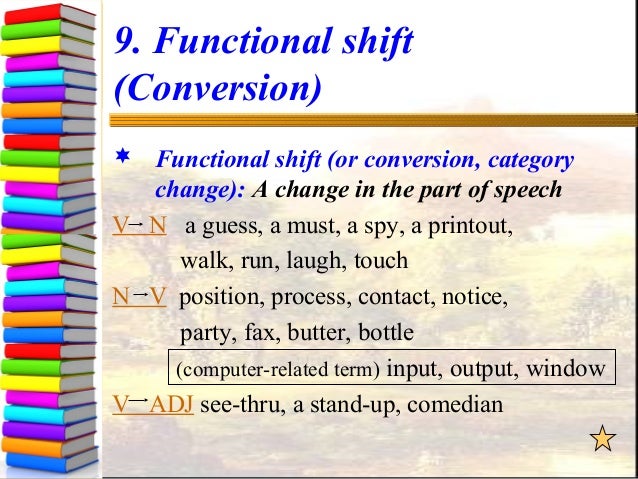

There can be no doubt that language is a living entity that changes over time. One example of how a language changes is the functional shift. Basically, a functional shift occurs when a word that is already identified and used extensively in one manner begins to acquire a second use that is of a completely different nature in both the spoken and the written word. Here are a couple of examples of how a change in syntax can lead to a functional shifts that over time become acceptable components in the common grammar of the day.

One fairly common occurrence with the event of a functional shift is that a word that is normally identified as a noun beginning to take on usage as a verb, or vice versa. There are a number of examples of this type of functional shift. Commute is only one of many words that can be used as both a verb and a noun today. As a noun, a commute refers to a journey or trip that is taken. As a verb, commute can refer to the act of taking that trip, as well as foregoing something, such as commuting a sentence or an obligation.

A functional shift can also occur when a preposition that is normally used in comparisons begins to find usage in the form of a subordinating conjunction. The word “like” is a classic example of this type of metamorphosis. As a preposition, “like” can be used to compare the action of one thing to another. As an example, “he runs like a horse” helps to compare the running habits of one living entity to the running prowess of a different live animal. At the same time, the word “like” may be used to suggest intent. “He sounds like he means it” carries the same meaning as stating “he sounds as if he means it.”

Definition of functional shift.: the process by which a word or form comes to be used in another grammatical function.

- Abstract Lateral functional shift of the mandible is characterized by transverse rotation of the entire mandible about a vertical axis toward 1 side of the head.

- Functional shift - WordReference English dictionary, questions, discussion and forums.

- Shift functions horizontally and vertically, and practice the relationship between the graphical and the algebraic representations of those shifts.

One of the fascinating things about linguistics in general is that the science of languages is a discipline that is forever evolving. No language has ever remained static for very long. As generations pass, words that once held only one meaning and style of usage in the written and spoken word will begin to take on other applications. The occurrence of the functional shift is recognition of that evolution, and one of the characteristics of a living language that keep our chief means of communication exciting and fresh.

Without a doubt, Shakespeare is one of the most influential writers to publish in the English-speaking world. His works have been interpreted, analyzed, deconstructed, and re-imagined for the past four centuries. Because of the extensive popularity and extensive research that has been applied to his works, it would be hard to find a better alternative than Shakespeare, when studying literature and the brain.

In 2006, Phillip Davis, editor of The Reader magazine and professor at the University of Liverpool, set out to see how Shakespeare effected us mentally. Teaming up with Professor Neil Roberts of the Magnetic Resonance and Image Analysis Research Centre, they decided to study the linguistic phenomenon called the “functional” or “Shakespeare effect”. This effect happens when the function of a word changes, such as a noun to verb, or an adjective to verb. For example:

King Lear: “He childed as I fathered” (noun to verb)

Othello: “To lip a wanton in a secure couch/And to suppose her chaste!” (Noun to verb)

Modern Times: “I just googled the entire plot to Midnight Summer’s Dream. It was ok.” (Noun to verb)

According to Davis, research shows that the brain processes verbs and nouns in different place. Thus the question was: what happens when you muddle with them?

Picture of EEG sensors. Fun fact–UI uses these for research, too!

Using electroencephalogram (EEG) tests, scientists discovered that this functional shift had a profound effect on the brain. They found out that the brain sensed both grammatical and semantic violations, and when it did, it lit up the brain in different places. When there were grammatical errors, the brain released a wavelength called N400, and when semantically it was wrong, it released a wavelength called P600. What was unique about Shakespeare was that reading of his literature produced high P600 waves because of the functional shift, a wavelength that does not get released often in people’s brains today. This is significant, as Davis explains, because:

“In other words, while the Shakespearian functional shift was semantically integrated with ease, it triggered a syntactic re-evaluation process likely to raise attention and give more weight to the sentence as a whole. Shakespeare is stretching us; he is opening up the possibility of further peaks, new potential pathways or developments.”

And EEG is only the start. MRI and magnetoencephalograhy (MEG) studies of the functional shift’s effects in the brain are underway at the University of Liverpool. This is extremely relevant and exciting research. Too often, people underrate the importance and value of language and reading for brain development. With STEM studies seen as something for “smart” people, all too often do people shed a bad light on the value of humanities. This research shows that the value of literature to personal development should not be belittled. Literature invigorates, challenges, and strengthens brain passageways in ways we are just beginning to understand. And amazingly enough, Shakespeare, though now four centuries past, is at the helm of these scientific discoveries.

Works Cited

Davis, Phillip. “The Shakespeared Brain.” More Intelligent Life. The Economist, 2008. Web. 11 June 2015. <http://moreintelligentlife.com/story/theshakespeared-brain>.

Keidel, James L., Philip M. Davis, Victorina Gonzalez-Diaz, Clara D. Martin, and Guillaume Thierry. “How Shakespeare Tempests the Brain: Neuroimaging Insights.”Cortex 49.4 (2013): 913-19. Web.

Nightshift Forum

University of Liverpool. “Reading Shakespeare Has Dramatic Effect On Human Brain.” ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 19 December 2006. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2006/12/061218122613.htm>